WWOOFing in Norway: Odds and Ends

It’s been almost a year since I went to the conference in Munich that started all this and I’m getting self-conscious and kind of ashamed that I am still writing about a 2 month experience over a > 6 month time span … almost 12 months later …

To put this post in perspective, this (probably the last) part of a series of posts about WWOOFing in Norway so far:

- WWOOFing in general

- Farm work we did

- Things we did in our free time

- Odds and Ends <— You are here!

This post will be a compilation of micro-stories that fell through the cracks.

Part A: Misc tasks in Gjøvik

It seems like most tasks fall into one of two (or both) categories: expansion or maintenance. Maintenance tasks are associated with periodicity: be it once a day, or once a decade. Expansion tasks are one-off campaigns associated with a goal. Typically you’d hope that work you put into the expansion leads you to a new “normal” that is better than you began with, whatever “better” means to you.

For a person, maintenance tasks include pooping, sleeping, eating… basically, surviving [1]. Whereas “learning” would be an example of an expansion task [2]. For the farm in Gjøvik, daily maintenance tasks include watering, harvesting, weeding, and tending to chickens. Whereas all the sub-tasks associated with expanding the Food Forest are obviously expansion tasks. Besides these, here are four miscellaneous tasks we had to do that simultaneously happen to highlight distinct elements of a permaculture farm.

[1] Augh, it’s actually so annoying that so much time it takes in a day is “wasted” just to survive

[2] Being on top of the maintenance tasks while still leaving yourself the capacity to work on expansion tasks is an art of living. It’s also really interesting to see what kind of negotiations people make. For example, some see eating as strictly a “maintenance task” and survive off Soylent. Meanwhile, others would spend exorbitant amounts of time and money chasing culinary experiences as if it were amassing them is an “expansion task”.

1. Chickens

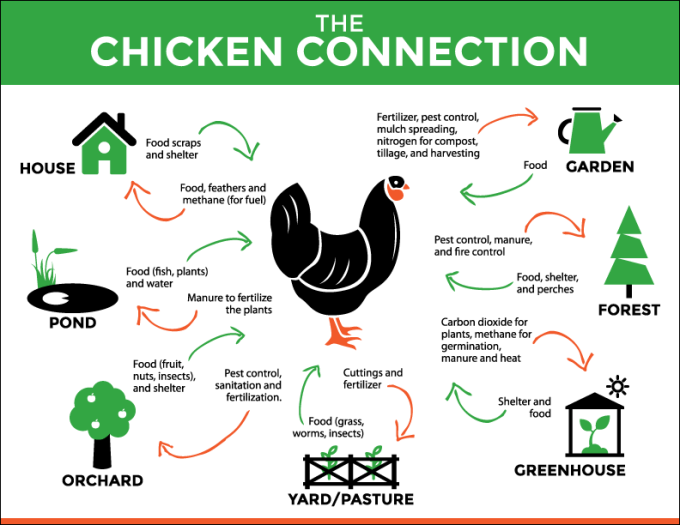

Permaculture peeps consider chickens, not pipsqueaks, but powerhouses. Chickens are more often than not the token example of permaculture principles at work. Chickens embody every tagline that permaculturalists endorse … let’s see how many I can fire off off the top of my head:

- “every element should have multiple (at least three) functions”–chickens control pests by eating them, scratches the ground (and loosens it), not to mention … eggs!!!

- “see waste a solution rather than a problem”–chickens help compost our food scraps faster than a composter would … AND their poop adds nitrogen into the soil!

- “work with nature not against it”–chickens pretty much replace fertilizers, pesticides, and tractors

- “everything is connected”–the chickens benefit from our outputs, and the outputs of the chickens benefit us!

Source: Abundant Permaculture

It goes without saying, that in both Gjøvik and Tønsberg, chickens were part of our daily “maintenance” tasks. Chicken needed to be fed daily and their pens needed to be moved periodically so (a) they can scratch at a different patch of earth each day (“tilling” and removing pests) and (b) their nutritious poop can be distributed over the field! Oh, and of course we snagged their eggs. Chickens are actually really low maintenance, especially if you get smarter types that haven’t been bred for the sole purpose of shooting eggs out of their butts like machine guns *cough*conventional farmers*cough*.

One sunny Saturday afternoon, we even got to give the chickens a bath … which is perfect because Saturday is Lørdag in Norwegian and the “lør” in Lørdag means “bath”. (I guess Vikings only took baths once a week.)

By some cosmic irony, I have been self-identifying as a “Chicken Activist” since grade 5, albeit for different reasons. Back then, it was because I would always be the first to “chicken out”. From watching horror movies to breaking rules, from using knives to attending piano lessons without practicing … I’d be “too chicken” to do any of that. I was (and am?) an all-round “chicken”, “birdbrain” included. At some point, I decided to embrace the label. After all, the only way I can continue to chicken out of things I was genuinely afraid of was to have zero cares about what what people think is to be shameless. In fact, chickens will henceforth be my favourite animal, I decided. Eventually, this unapologetic attitude evolved into full-out chicken advocacy. I decided that if people had specific “causes” they defended … like “polar bears” or “whales”, my cause would be the chickens. I would advocate against their defamation: it’s not that people don’t deserve to be taunted “chicken”, chickens don’t deserve to be associated with us ‘fraidy cats [1].

All this is to say that today, I see Chicken Activism in a slightly different light. Chickens don’t only have a place in my heart, they ought to have a place in my backyard!

[1] Obviously, I had no problem with the defamation of cats

2. Woodchips

Another task we had was to prune some of the trees at the edge of the property.

Left: sawing off a branch. Right: Branches are just small trees ……. are trees just fractal patterns???

The trees were destined to be chewed up by a woodchipper and turned into woodchips. Woodchips are used to mulch the Food Forest and will simulate the humus on a forest floor. I’ll let this guy explain … (Speaking as a friend to a friend, you only need to watch the first 5 minutes or so to get the point. Trust me.)

That’s literally the same video our hosts showed us to evangelize woodchips.

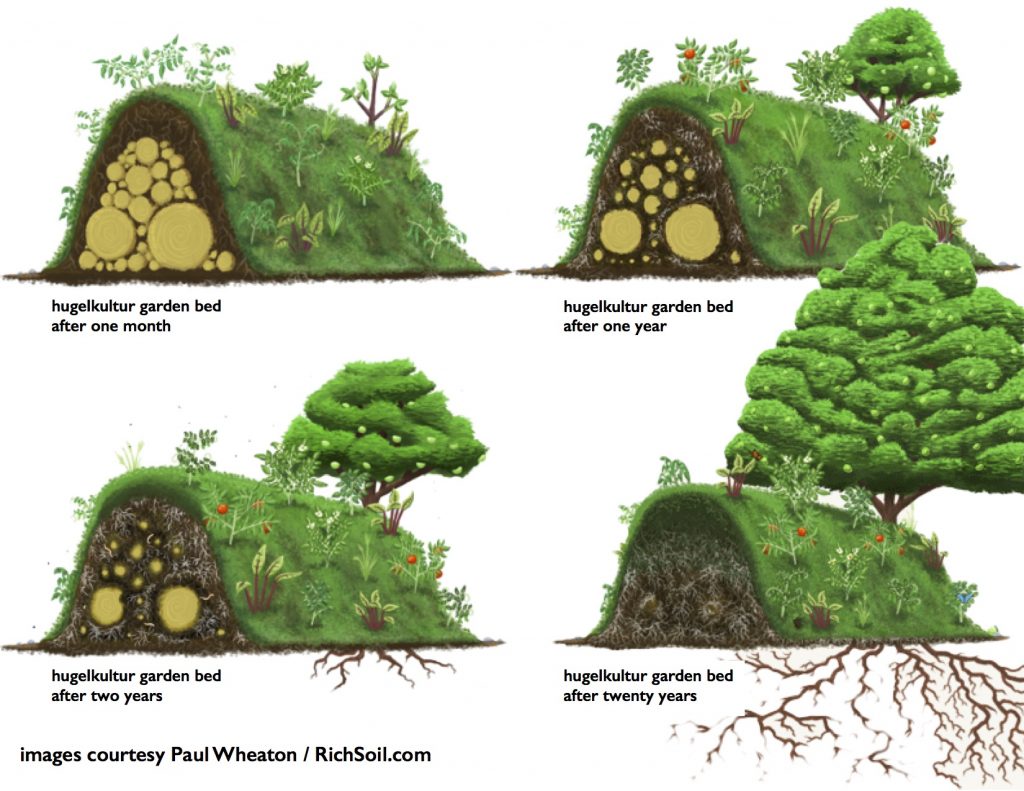

Moreover, the long logs can also be used for hugelkultur garden beds which our hosts also had an abundance of. Again, taking inspiration from the forest, the idea is to make use of the decomposition process of dead logs to attract beneficial insects, fungi, etc. that will add nutrients to the food you grow on it.

Source: RichSoil

3. Compost

It would be remiss of me to write 8 posts on my WWOOFing experience without once mentioning compost. If the guy in the YouTube video is crazy about woodchips, our host was crazy about compost!

There were several composting experiments going on in the farm: Bokashi (anaerobic), Berkeley (hot), Vermi (worms), and Cold. Cold composting is the super-beginner gardener way of composting (aka. leaving everything in a pile in your backyard). Bokashi composting involves adding some sort of bacteria and yeast to fermented the compost. Vermicomposting (worm castings) makes super nutritious compost…. with potential for exponential compost generation as the worms reproduce and stuff. Berkeley’s perfected method seemed to be our host’s favourite pet project … it’s supposed to make a LOT of compost in a SHORT amount of time by monitoring the chemical composition, frequency of turning, and size of the pile. Because the middle of the compost pile gets so hot, our host was even toying with the idea of running water pipes through the compost pile for compost-heated water! In fact the compost pile got so hot, it started burning in the middle … yikes! (that’s also why you need to turn it once in a while)

As far as our involvement, twice a week, this Lefse-bus will come and deliver us all their potato skins. We’d have to scrape the bins of skins and rotting potato into a dumpster… which our host will incorporate into his Berkeley compost pile!

4. Resourcefulness

Of course chickens, woodchips, and compost are resourceful in systemic, supported-by-science kinds of ways are therefore already in use (or at least been considered) by any self-respecting organic gardener/farmer. However resourcefulness can be applied locally as well as universally … ’cause “it’s a mindset”, yo [1].

On a particular day, we were asked to build raised garden beds as a temporary nursery for some plants.

building garden beds

This was when we learned that garden beds were actually once people beds. In 2016, Lillehammer hosted the Youth Olympics. The beds were used by youth Olympians for the duration of the event, but after the event, they had to be dumped. Our host rescued over 30 of these beds from this fate.

After building one of these beds, we realized they not only were all the other garden beds Youth Olympic reject-beds … but the beds we’d been sleeping in for weeks were also from the same cohort of reject-beds.

beds for growing plants and growing humans alike.

To share common needs with these baby plants is both a humbling and a beautiful thing.

[1] Pet Peeve alert: “X is a mindset”, “X is an attitude”, “X is a way of life” all variations of similar things that people say when they consider “X” is something so positively wonderful/integral to their identity that they resist defining it altogether.

Part B: Misc tasks in Tønsberg

I’ve never really gotten a chance to share about the projects we worked on in Tønsberg. As a garden than a farm, there are less specifically “pastoral” things I could elaborate on, but as you can see below, we definitely got to work on more constructive things (that required finer motor control) in Tønsberg as opposed to destructive things (that only required brute force) Gjøvik.

I think I’ll have more to say about permaculture in general in due time. However what is apparent from our 1.5 months here is that permaculture homesteaders/farmers invest a lot of time (and money) upfront on expansion projects in hopes to build resilient systems that can maintain themselves in the (really) long run (say, 30 years in the future).

I guess that strategy makes a lot of sense… but a lot of (often conflicting) things are calling for our attention/action/money now by, similarly promising a return on that investment in the future. For which of these promised futures should I allocate my present resources?

Ultimately, It takes a lot of faith in one thing or another (science? humanity? capitalism?) to bear the present cost for a promised future. It’s obviously faith in something that propelled our hosts to uproot their lives and spend so much time/money in hopes of a more resilient future for their children (and the Earth!) decades later.