Organics for the Care for our Common Home

This semester I have the opportunity to formalize some of my past year’s gardening experience by taking the Organic Master Gardener online course through Gaia College. This weekend I had the privilege of attending Guelph Organic Conference. Both activities were mutually informative and are giving me a lot to think about (so much so that I have to write about it!) and I am so grateful that my employers would sponsor my personal and professional development in these ways.

Just to note, I may be using “regenerative” as a placeholder where others would be using “organic” in the course/conference [1]. Throughout the gardening course and conference, the word “organic” was often used to imply some sort of motivation to nurture the land relationally; sadly, organic labeling and certification often strays from this spirit by distilling relationship into dogma. Augh, nothing is new under the sun.

[1] If I understand correctly, there are slightly different focuses associated the two terms, but a lot of their goals overlap.

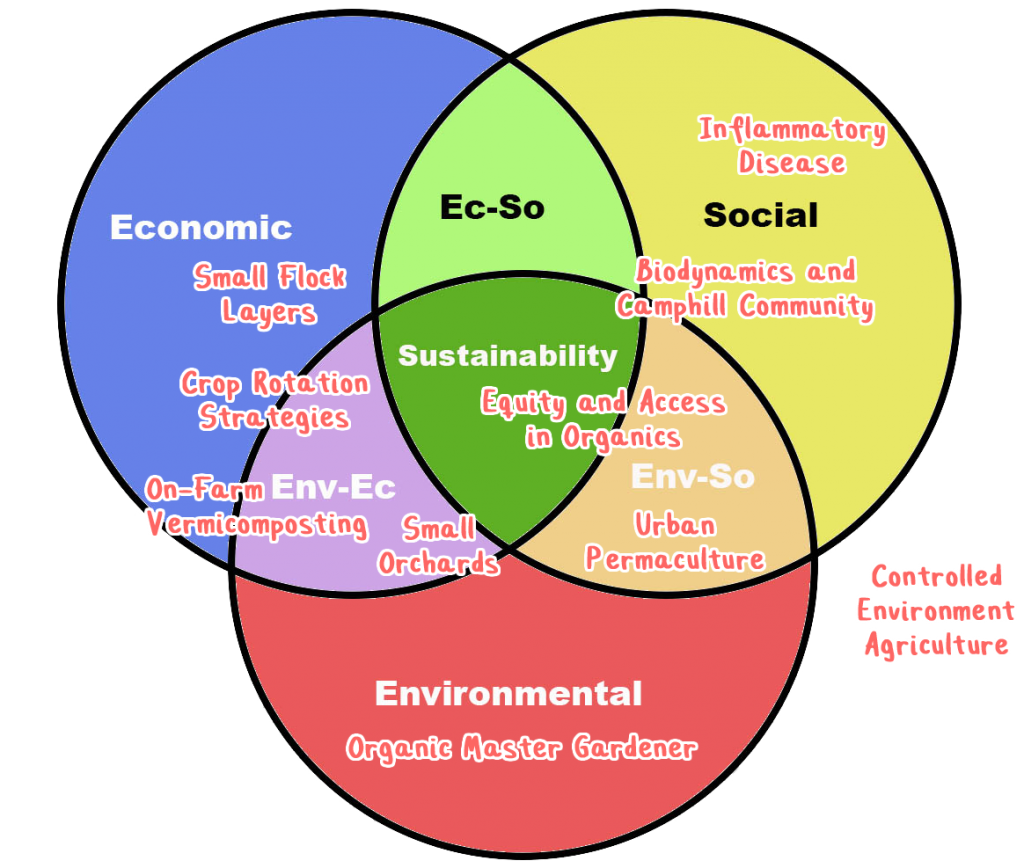

I think it’s instructive to consider that regenerative enterprises seek to meet a triple bottom line of ecological health, human health, and economic sustainability. With regards to the Guelph Organic Conference and the Organic Master Gardener course, it’s interesting to see these goals emphasized in different proportions. I’ll elaborate on some of these below.

Controlled Environment Agriculture’s Triple Bottom Line

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) markets itself to laypeople (using often in sensationalist Facebook videos) as the future of food: close-looped systems that grow in warehouses. Without soil. Without sun. Towers of vegetables that are grown and harvested automatically in substrates that have that signature Apple-aesthetic.

I’ve written about controlled environment agriculture before. Back then, I had hunch that CEA is not the direction I would vouch the future of food system to steer towards, but didn’t know enough about it to write it off entirely. After hearing Evan Bell‘s talk on Controlled Environment Agriculture – Trends, Risks, Impacts, I am more aware of the multiple dimensions of hype, the ulterior motives, and more realistic expectations on its ROI. Me being me, I am always most disgusted by ulterior motives (hype would be a close runner-up). It follows that these tidbits disturbed me most:

CEA and the Social Bottom Line

CEA is a playground for retired men from the tech industry to hi-jack “food justice” as a noble excuse for an otherwise egoistic tech challenge. Evan also made a great point about how growing lettuce for the Inuit is rather culturally inappropriate. Meanwhile, CEA is being marketed as a solution to the food price issues in the North… (perhaps harvesting the fish rather than the lettuce from an aquaponics system that would be more realistic!)

Now that there is hype around CEA on its own right, many people are divorcing the technology from its original food security motivations. There are new “personalized” counter-top hydroponics systems for sale so the bourgeoisie can get custom herbs on demand, after having coffee from their Nescafe and Keurig coffee machines.

CEA and the Environmental Bottom Line

I will recognize that there is a place for CEA to reduce the distance traveled by our imported foods, produce vegetables year-round (in dry and/or cold environments), and make use of brownfield classified urban spaces. However, Debbie Downer over here (hello!) is always concerned with motives.

See, the general rationale for using CEA is the following: thanks to climate change, the variables (sun, air, water) required for growing food are going haywire; if we can’t rely on nature for consistency, we must manufacture the most consistent, most controlled environment on our own. Therefore, CEA turns a farming problem to a manufacturing problem.

Aside from the hubris of assuming plants will do better under our sterile micromanaged conditions, we are intentionally separating plants from years of co-evolution with soil microorganisms and free energy from the sun… That’s kind of dumb. Practically, there are tons of pitfalls and challenges when you deliberately remove a whole system that depends on the sun away from the sun.

Aside from the cowardice of running away from human-induced climate change, we are doing nothing to face or counteract it. Thanks to conventional agriculture we’ve already pillaged the fertility from our land, and now we’ll just retreat into our concrete jungles without adding any organic matter back… That’s kind of selfish. CEA might be a replacement for conventional agriculture, but it’s not an alternative to regenerative agriculture.

CEA and the Economic Bottom Line

Actually, CEA might not even be a replacement for conventional agriculture.

CEA needs to be funded by large companies or venture capital to operate at economically sustainable scales. Most people are drawn to this market for “value” reasons (ie. social and environmental) rather than economic reasons. However many of these enterprises fail because the ROI on veggies conducive to growing in CEA conditions is not high enough to elicit the cost to set up the system unless they are sold to these larger companies.

Evan showed us CEA examples funded/bought out by McCain, the Royal Family of Saudi Arabia, and even Elon Musk’s brother. Apparently, these companies aren’t making much money off their CEA projects either, they just have the capacity to fund such projects–in the name of “food security”–as PR stunts. Yet the fact that these companies are funding CEA rather than regenerative agriculture is indicative that they are co-opting the food security message to justify their vanity. The collaboration between Google and Vancouver was a particularly epic epic-fail.

Ultimately, there are good and profitable CEA enterprises out there made run by the “little-guys”. And there are opportunities for CEA enterprises to reduce costs by establishing symbiotic relationships with other industrial processes (ie. coupled with a paper mill for reduced heat and hydro needs), which I suppose is a way of moving towards a more relational attitude. We need to think critically so that we can support the genuine peeps over the “hype beasts”.

Regenerative Agriculture’s Triple Bottom Line

4 years ago I began thirsting for expressions of faith (and humanity in general lol) that are different from what my own faith community publicly endorses [1] when I stumbled upon “eco-spirtuality” [2] talks about the Pope’s Encyclical On Care for our Common Home at the University of Toronto. While I still don’t have romantic notions of Nature (with the capital N) nor am I well versed with Biblical rationales for caring for the earth [3], there is an unarguable Biblical call to identify with the oppressed. Globally, the poorest and most marginalized are those most affected by the downstream effects of environmental degradation–is this connection alone not enough for people of faith to be moved?

At the Guelph Organic Conference, some of these familiar faces like Dr. Stephen Scharper and Heather Lekx (Farm Manager at Ignatius Farm) convened at the Equity & Access in the World of Organics panel. It kind of felt like coming home, like my explorations over the past few years have come full circle.

Environmental

Taking the Organic Master Gardener course has done well to convince me to move away from interacting with nature on a mechanical basis and towards living in relationship with nature.

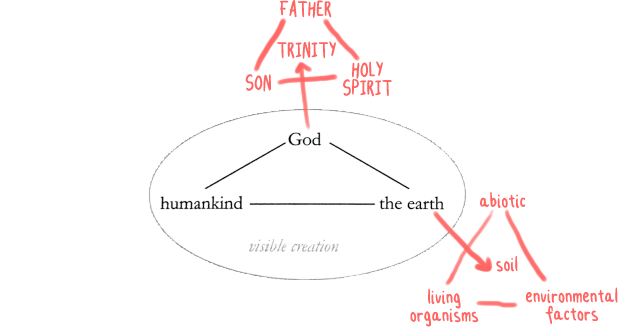

For example, conventionally we are taught that soil is a lifeless by-product of a mechanical process of erosion. However, our textbook explained soil as a relationship between three parties: a-biotic components, living organisms, and environmental factors; and we should have a relationship with our soil as a result. This is going to sound sacrilegious, but on one hand, it reminds me of the Trinity, where the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, are often described as being in “perfect relationship”. On another hand, Sunday school teachers have been proselytizing that I ought to strive for a “relationship” with Jesus. Well it turns out I ought to be in right relationship with everything.

(Sacred Earth Sacred Community, pg 176) + some arbitrary connections from yours truly.

Seeing as everything is related to everything, it’s hard for me to summarize anything in a linear manner. Here are some highlights, though:

- Pests are nature’s way of recycling unhealthy plants. The best way to prevent pests is to keep plants healthy. Pesticides are not only myopically treating symptoms only, but also disrupting beneficial relationships in its vicinity.

- Fertilizers flood the soil with nutrients that tend to displace existing nutrients. Displaced nutrients can run off and leech into our water systems. Fertilizers often provide the right chemical components in configurations that cannot be absorbed by plants. This, too, becomes run off.

- Humus and organic matter has a greater capacity to hold cations (positively charged nutrients), anions (negatively charge nutrients), and water than virgin soil (sand, silt, clay) can hold alone. Regenerative practices promote biodiversity in the soil which in turn increases the organic matter in soil which increases the soil’s capacity to hold water, reduce flooding, and keep nutrients from running off.

Consider this video. Not only does irrigation without covering the soil with organic matter not infiltrate the soil deep enough to be useful for plants in the long run (which has visible effects on our local gardens), but it also doesn’t contribute to ground water (which has invisible effects on the broader ecosystem). Furthermore, the scoop used to represent a “pump” reapplies both the water run-off and the eroded soil, however in practical applications, I’d think the soil would be filtered out of the pump–in which case only run-off water is replenished, but eroded soil is not. On the contrary, organic matter mulch passively slows down the water enough to substantially infiltrate the soil and deposit excess towards ground water.

Finally, I am always weary of using tables that simplifies things as binaries in opposition. But I include the table below because it makes clear where stuff like CEA stands. If conventional agriculture is a by-product of the Industrial Revolution, then CEA is the I.T. Revolution’s iteration of conventional agriculture (and therefore not regenerative).

| Conventional Agriculture | Regenerative Agriculture |

| Mechanical Pest management Monoculture Fertilizers | Relational Health management Biodiversity Organic Matter, Effective Microorganisms |

Human/Social

Whereas the mindset that desires environmental justice considers relationship globally, the desire for food justice looks at relationships locally. Globally, vulnerability to environmental damage is dictated by power and privilege. Locally, the distribution of nutrition is also determined by power imbalance.

In tandem with recently realizations on the human gut microbiome, it follows that a diversity of beneficial soil microorganisms leads to beneficial plant microorganisms which leads to beneficial gut microbiome upon consumption. Plants are grown in a soil ecosystem filled with beneficial microorganisms and plant-available nutrients etc. are bound to have superior nutrition… soil health is so intimately connected with human health! By contrast, produce grown conventionally are practically symbols for the real thing they represent. (Not to mention, all produce today will have higher carbohydrate to nutrient ratios than they did historically simply due to climate change).

| Conventional Medicine [†] | Regenerative Mindset |

| Human as machine Disease/symptom management | Humans in relationship Health management |

[†] As a caveat, sometimes I think it might be problematic to draw equivalence between conventional medicine to convention agriculture. The mindset is similar in many way, but I think it might be dangerous if we start trying to draw parallels between vaccination and synthetic pesticides/fertilizers… just sayin’.

The Inflammatory Disease talk at the conference represented a pretty alarmist stance at the implications of nutrient and microorganism deficient food on diseases that we wouldn’t normally associated with diet (ie. learning disabilities, cancer, etc.). However, if the health implications of regeneratively vs. conventionally grown food are as divergent as claimed, I find it that much more deplorable that the products of regenerative agriculture (ie. “certified organic food”) are not accessible to the poor and marginalized. Those who have to eat food that will make them sick can’t even afford the “healthcare” that will hide the symptoms. Just as it is empowering and socially/morally-glorifying to buy something that will beneficially the health of ourselves and the planet, it’s disempowering to not have access to it. Regenerative agriculture alone does not address issues of social exclusivity.

Ignatius Farm addressed this concern beautifully in the Equity & Access in the World of Organics talk. Ignatius Jesuit Centers were historically religious institutions with dispositions towards social justice and education with no specific agricultural calling. They had farmlands simply to support their primary endeavours, and when conventional farming came along, there was no need to upkeep these farms… this center in Guelph was an exception! Since then, the center has been repurposed with a specific focus on ecology, but they’ve continued to contribute to the welfare of their community.

Economic

The immediate difference between the Organic Master Gardener course and the Organic Conference is scale. Whereas the course is more applicable for backyard gardeners like myself, the conference caters to organic farms and small businesses. When considering vermicompost, crop rotation, and raising chickens on a farm scale, I can understand how economic viability is of utmost importance. Still, it bothers me when biological success is merely stated as a cute by-product of business success. Ironically, a number of conventional farmers were at this conference because they’re finding that their land is no longer producing when they farm conventionally, they’re coming to this conference because it regenerative practices make economic sense.

Dr. Stephen Scharper ended the Equity & Access in the World of Organics panel with a note on the role of religious groups to drive solutions outside typical market dynamics. He gave the example of how the Anglican Church partnered with the Parkdale Land Trust to purchase a property way below market value to start a community agriculture project that empowers locals and immigrants and put a damper to gentrification in the area.

Hearing the work of Ignatius Farm and Anglican Church of the Epiphany and St. Mark gives me hope in light of what happens all too often:

People often seek a solution by assigning political action to the individual Christian and confession to the church. Obviously, there are different mandates, primary for some and secondary for others, and they are not simply interchangeable. But total separation would be dangerous, and cannot be maintained under any circumstances. For the church may be in danger of becoming abstract and docetic; and, as history has shown time and again, it may end up as an accomplice of reckless power. And the individual Christian, left alone, will be exposed to many practical and spiritual perils.

Friendship and Resistance: Essays on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Eberhard Bethge

[1] Rant: Our explicitly “Chinese” church often turns to middle-class American men telling us how to be a Christian, how to be healthy, and even how to be married via cheesy-ass videos and patronizing workbooks. They say that these resources are only a “framework”, but the “framework” is still is the starting point, it’s the “neutral” stance from which all other expressions of faith are “deviant” or “more specialized”. That’s why we need abscess to describe “black liberation theology” whereas “white male theology” is simply “theology”. How we choose what our “framework” will be is not innocently decoupled from power. But I digress…

[2] Note that it’s “eco-spirtuality” instead of “spirituality” because it’s still not yet generally accepted that care for the earth is considered a subset of being a person of faith.

[3] There are many such arguments that are intellectually stimulating in their own right. However I think it’s a privilege that we can even debate whether we need to care about the earth for lofty reasons like “because heaven will be on earth” etc. without having to deal with the tangible consequences of climate change etc. Meanwhile the “earthly” effects of anthropogenic environmental degradation are so well-hidden from our affluent urban centers.