Food Forestry in Gjøvik

Our first expansion project in Gjøvik was to help expand the Food Forest.

The idea of the Food Forest (or Forest Garden) is to look to a naturally occurring forest as inspiration for how vegetation should be organized in a garden. Notice all the diversity and connections that exist in a forest: multiple levels of shrubbery, thick humus that keeps water in the soil, animal life, perennials that grow deep roots in a forest.

Our permaculture peeps see the connections and positive feedback loops between all the aforementioned components and are inspired to replicate this system using edible plants. By intentionally planting layers of mutually beneficial, edible and non-invasive perennials, they hope to improve soil quality and create a resilient food system that requires less manual inputs over time. “Harvesting” would be more akin to “foraging” in a forest of food like this! [1]

[1] Compare this to monoculture: neatly planted rows of shallow-rooted annuals that suck up the nutrients in the soil and don’t add anything back. They require active manual irrigation, synthetic fertilizers that are eventually leeched into our lakes, pesticides that are merely less toxic to us than the pests, machinery further compacting the soil at every step–but I digress.

Specific ecology knowledge aside, the manual labour of making a food forest seems easy enough:

- lay some cardboard over the grass

- add some horse manure

- plant your perennials

- mulch

But oh, how naive you are, reader-of-DIY-forest-gardening-books (aka me).

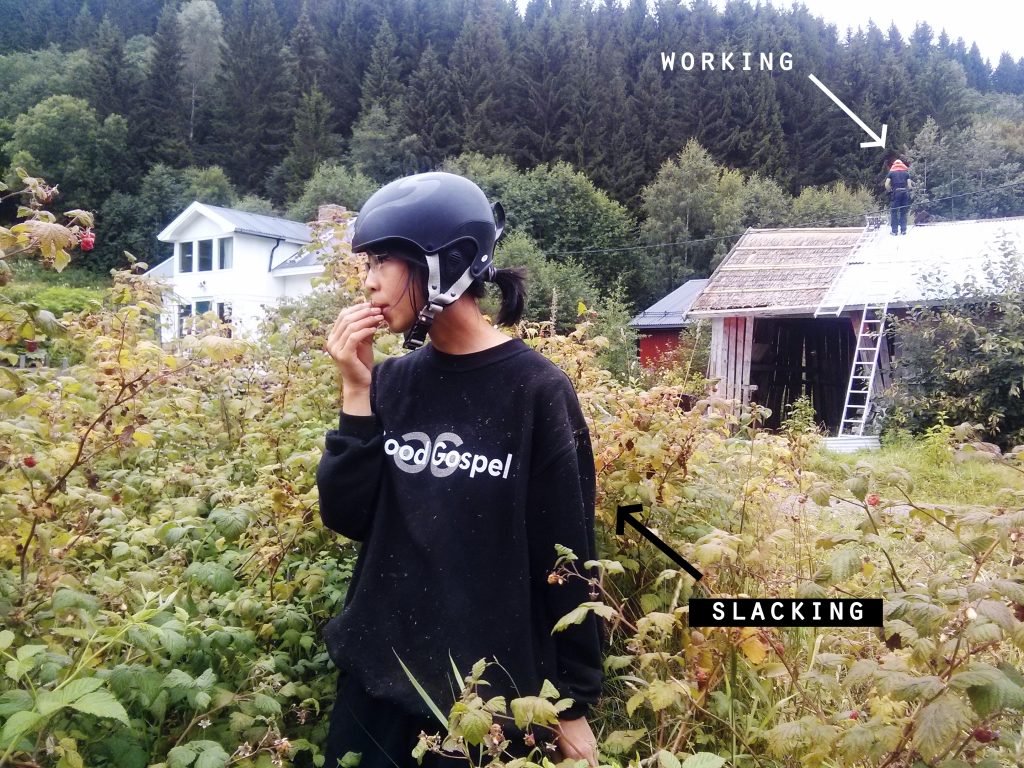

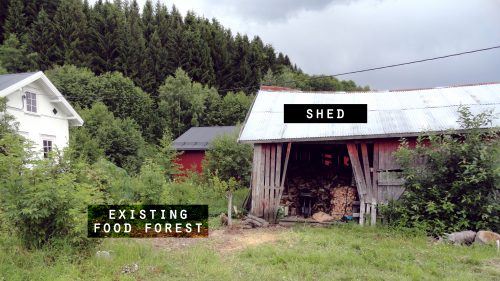

Every plot of land has its own peculiarities to work around. In this case, in order to expand the food forest, we needed to tear down this old shed that was next to it.

while it may look like the food forest is just a compilation of weeds/foliage, everything planted there was intentionally chosen and everything these is edible! The idea is that over a long time (on the order of decades) it will continue to mature into an actual forest.

But in order to tear down the old shed, we needed to clear out and sort all the garbage in it.

Only after those could we tear down the old shed

and finally lay cardboard down.

Let us take a look at the true order of operations:

- clear out the firewood in the shed

- (a) arrange logs neatly into log bags

- (b) move neatly stacked bags out

- clear out garbage inside shed

- tear down shed

- (a) tear down walls

- (b) tear down roof

- (c) take out foundation

- clear out garbage under shed

- expand forest garden

- lay some cardboard over the grass

- add some horse manure

- plant your perennials

- mulch

Notice how the original, anticipated order of operations is a much smaller subset of the real order of operations (5-1 to 5-4)? In fact, we had to leave after leading down the cardboard (step 5-1) so we never got to plant anything! Come to think of it, most of our work was actually destructive (getting rid of old things) rather than constructive, haha.

Meditation 1: Progress and Catagenesis

For an engineering course, we had to read The Upside of Down which really drilled home the point that there is a destructive component to progress. The author referred to the phenomenon of having to destroy the old to create the new, catagenesis. Evidence was drawn from ancient civilizations and empires that had to be overextended and collapsed before something new could emerge from the ruble.

With regards to expanding this food forest, we were clearly in the destructive arc of that narrative.

As we excavated the “empire” that existed before our hosts bought the property and are in the process of reforming it according to permaculture principles, we couldn’t help but try to understand the previous property owners who “reigned” during the post-WWII era. We excavated all the symptoms of industrialization, capitalism, and mass consumer culture–packaged goods (coffee, random jars of stuff), the beginnings of fast fashion (old boots and work clothes), paper, old car seats and tires … but the fact the previous owner dealt with the sudden influx of material by simply building new sheds to store everything (apparently our hosts tore down 3 other sheds–ALL filled with garbage–before this one!) indicates that humans’ adaptation to industrialization lagged decades behind the actual event. The people who lived before mass consumer culture grew up frugal and kept everything “for rainy days” … however these attitudes persisted (and even soured into hoarding) after material acquisition became much more accessible.

Looking forward at the trajectory of this property, I wonder if we are seeing the beginnings of a “new empire”. One that rejects material culture, returns to frugality, and demands simplicity… but this time, not because we must, but because we can?

Nah. It is because we must.

Meditation 1: Progress and Predecessors.

Like many of my fellow millennials, I often resent the “mess” our predecessors have “left us with”. Perhaps this resentment is ill-placed.

I think each generation had their own urgent problems they had to deal with and overlook less urgent matters like those that created that “mess”.For example, to expand the Food Forest, we took a good several days just to stack logs nicely into log bags. It might have been natural for us to think, “wouldn’t it have been more efficient for everyone if the people who threw the logs in here just stacked them while they were at it?” Yet, we didn’t feel resentment that the logs were not stacked. We understood that whatever space the logs previously occupied needed to be cleared more urgently than the logs needed to be moved property.

From this, I gather that I ought to give my parents’ generation (read: first generation Chinese immigrants) more pardon for their strong (read: borderline forceful) recommendation for stability [1]. My parents’ battle was to make ends meet. They know more viscerally how one mishap can lead us into poverty and truly believe it is best for us to have cushy 9-5 jobs and modest emergency funds to keep ourselves from falling into poverty. In that light, I don’t consider their wishes for me to succeed in a material/social status kind of way selfish at all. In fact it’s quite selfless to work at a decent paying position you don’t love (as opposed to an insecure position doing work you love) if you fear that one mishap may force you to rely on and be a burden to others. That said, the decisions I make that undermine security look like naivete at best, and a middle-finger to their own life choices at worst. Being a benefactor at the other end of all the difficulties they had to overcome to immigrate to North America to have more economic opportunity–is not something I should ever take for granted.

My parents needed to be complicit in exploitative social structures (by doing work that contributes to our destructive consumer culture) to make ends meet for our family–that was the urgent thing that had to be done. Letting the rich get richer (and the poor get poorer) in the process was beyond what is politically and economically feasible for them if their own lives and families are at stake. But because of their success, I now have the freedom and privilege to look for work that is beneficial–or at least not detrimental–to the earth or the marginalized.

Ultimately, it’s because the previous WWOOFers were successful with doing whatever they needed to do that we had to capacity to work on expanding the food forest at all. Similarly. It’s because my parents’ were so successful at overcoming their hardships that I have a capacity to ponder the consequences of my participation in society beyond my own economic well-being. I need to listen to their advice–solicited or not–with both respect and nuance.

[1] There’s a stereotype that North American Asian parents are very proactive about their children becoming doctors, lawyers, and engineers and going to great lengths to get their children into good schools for this purpose. These children are expected to find work experience in their field throughout their studies and have a relevant, high-paying, benefit-providing job lined up for them when they graduate. Although my parents don’t give me any pressure at all, I feel kind of selfish that I’m not trying to find a relevant, high-paying, benefit-providing job. I feel like there is an unwritten rule getting the most prestigious position possible is something that I owe my parents. The weird thing is that, when I actually think about it, none of the elders that I have actual relationships with (especially my parents) gives me flack for my reckless life decisionsprocrastination–it’s almost completely self-imposed.