Field Notes from this Season of Vegetable Growing

In the days following our high school graduation, my friends and I sat in a circle on a patch of lawn beside the school’s science wing where so many memories were made, feeling the weight of going our separate ways and savouring the last moments of normalcy. One of us suggested that we go around the circle brainstorming/imagining each others’ futures–where would so-and-so be in 10 years time? For some, we could unanimously envision specific accomplishments and lifestyles. Other futures provoked theory and debate, or teasing and banter.

Not a Pokémon, but you get the point. Source: We Have Our Dragons

My future? It drew blanks.

debbie

career: ??

marriage: ???

progeny: ?????

The unholy offspring of VeggieTales and Happy Tree Friends

I felt like a legendary Pokémon.

After some chatter among themselves, a voice rises above the mumbles that were slowing to a silence, “–I don’t know, I just see debbie in a lab coat.” There was neither agreement nor disagreement with that statement. (I was, however, voted “most likely to not attend the high school reunion”… so I’ve got that going for me.)

We are coming up to the 10th anniversary of that conversation next June. Friends then and since have now found places in society that are so authentically them. Educators, Consultants, Carpenters, Statisticians, Artists, Accountants, Missionaries, Doctors, Farmers, Scientists, Lawyers, Business Owners, PhD students, and–god forbid–even Engineers. Through my friendships, I see the possibility to be in professions in integrable, worthy, and admirable ways that do not compromise their selves. There is good work being done in the world–I can acknowledge that–but good work I cannot envision myself doing nevertheless. Like my high school friends, I also struggled with imagining a future that is an authentic expression of my self.

In this post, I endeavour to update myself since the post, Notes from this Semester of Human Becoming, when I had just finished two semesters of note-taking. I can’t say the future is any clearer, but I have enough distance to finally make some meaning of the recent past. As such, I’ve found it helpful to interpret my journey as a tumultuous process of (1) inviting crippling sorrow within and (2) learning to live through it anyway before (3) participating in life via work.

This post will have something to do with growing vegetables, I swear.

I. Sorrow

Several “talk therapy” sessions with various thoughtful people I trust have converged on the fact that I appear unemotional not because I don’t have emotions, but rather because I find my unleashed emotions too all-encompassing. To function to my desired efficiency in practical day-to-day life, I need to keep my emotional life separate. Even today, I only read fiction when I’ve allocated enough space and time to get fully invested in another universe; I need space to grieve when I return to this universe. If I had to be personally invested in every issue from fracking to sex trafficking, from deforestation to refugees, from polar bears to police brutality, I would be too paralyzed by grief to function.

Grad school changed this. In my first year in grad school, I desired to be more cognitively aware of social, political and economic systems; by my last year, I gave myself permission to be emotionally affected by the exploitation of the powerless and of the Earth that allows these systems to thrive. I realized that the overwhelming list of different “issues” people advocate are not in competition, but at its core are symptoms of broken relationships between human and self, human and humanity, human and the earth, and ultimately human and God. Now, I share sorrow with entities endowed with the same lifeforce I have are systemically oppressed. I feel remorse for all the ways I, too, am complicit in the systems that perpetuate and capitalize on broken relationships simply by being part of society. I feel resentment because there is no opting out.

For the ways society is currently organized, there is no amount of positive (let alone neutral) work I could do that could possibly “offset” the negative impacts I would have on the earth and on the marginalized simply by living my (middle-class sheltered suburban) life. Simply by living, I am participating in a food system whereby each person contributes an average of 4 tons of topsoil erosion per year. Not to mention energy, sewage, economy… anyone who can opt out and fully disentangle themselves from the negative by-products of being alive are themselves in some privileged socioeconomic position as a by-product of history (*ahem*Thoreau*ahem*), and therefore still complicit by virtue of benefiting from their power. We can all make our personal choices and negotiations, but at the end of the day to exist within systems of oppression–à la capitalism, colonialism, and all their subcategories–is to own some complicity over its functioning. I can’t help but wonder that if we even partially understood our complicity, we wouldn’t be so self-congratulatory every time we bought something fair trade/used renewable energy/helped someone for free/gave up our cars, we would grieve every time we couldn’t [1]. Grieving and mourning are not unproductive, they are forms of protest.

I used to suppress sorrow under the pretense that intense emotions would inhibit me from functioning in the world. Today, I embrace the sorrow because it inhibits me from functioning in the way the world expects me to. Today I see my sorrow as a nuisance to “get over”, but as an expression of love. I mean, at least I try to.

[1] Aside: Similarly, if we who profess a Christian faith even partially understood our complicity, we wouldn’t be so self-congratulatory (read: “rejoice”) when we show kindness (read: “show God’s love”) or “evangelize” or volunteer (read: “serve”), we would grieve. Grieve because our history has left legacies of trauma, grieve that people are still doing evil in the name of “good news” , grieve the cultural underpinnings of what we constitute as good news at all, and the cultural underpinnings that make us assume that others need it.

Lament is one of the most potent religious forms of reconciling us with out sentience in an efficacious way that names the pain of the world as our own, and demands justice be restored to the whole earth. … lament has a potentially catalytic and liberative function for our earth’s healing, if we use it as such. … In lamentation–in expressing our pain–we are often reconnected to that which we truly desire and love … Christians, who know the joy of the resurrection must be careful not to jump too quickly to the hope that lies beyond suffering.

— Living in Denial? Lament as Liberative Act, Marvin L. Anderson

II. Living

It turns out the tendency to go about calculating how I could possibly “offset” the negative impacts of my complicity in ecological and social turmoils has a name: scarcity mentality. Should I take the logical extension of those calculations, I should just opt out of life. Under a scarcity mentality, everything else would be better off if I don’t exist at all.

Still, we have to choose life over death. Because healing broken relationships is about choosing life over death. Because I, too, have life breathed into me that I need to stand for. Because those who benefit from the system would prefer to deny life from those who resist, those who threaten the system by existing. Because scarcity mentality and zero sum games need only be overthrown by imagination [1].

This season has taken me on a exploration of relational healing through decolonization. Decolonization is a practice of identifying power structures and subverting their narratives in our questioning, resisting their vision for our lives, standing in solidarity with its victims. On one hand, I need to live resisting. In this regard, I am already very keen on alternatives that already exist and are associated with fancy names like divestment, gift economy, voluntary simplicity, dumpster diving, van life. On the other hand, I need to live recognizing where I have power, authority, influence in my own life and use it to uplift those who do not. In this regard the “alternatives” don’t really have names or labels but are about how I conduct myself in relationship to people and the earth.

We are living in in-between times: though we may channel our living in resistance and solidarity, we are still complicit in the things we are resisting and the marginalization of those we stand in solidarity with. In the Biblical story, the Israelites fled Egypt (where they were slaves) to Canaan (the land God had promised them). However unfaithfulness and disobedience ensured and the Israelites were made to wander in the wilderness in between the land of slavery and the land of promise for 40 years.

The wilderness traditions of Exodus offer a vision of land in the midst of landlessness and a vision of hope in the midst of a hopeless space. The wilderness space is not just a space in between Egypt and Canaan, it is a space that is integral to the creation of social relations. In this vulnerable space of the wilderness, G*d’s unexpected gift of manna points to a vision of a future place (land) where no-one will grow hungry and no-one will lose hope. It reminds us that liberation from slavery includes the (un)promised space of the wilderness. To skip over the wilderness and move from Egypt to Canaan can risk creating a romanticized image of instant social change. By reclaiming the marginal wilderness, I am reclaiming a space where hope can be renewed in what may seem to be a hopeless place.

— New Creation in the Wilderness: The Space of Jubilee, Mario DeGiglio-Bellemare

As I continue to grieve the oppressive ways I inherited from “Egypt”, I also believe grace is extended to us in these in-between times–just as God provided manna to the Israelites in the wilderness. There is hope in the in-between. Though it feels like the are in-betweens in between in-betweens.

To survive, to dream dreams, to live in spite of sorrow is an expression of hope.

[1] Aside: Technology != Imagination.

If imagination is our problem, isn’t the most obvious solution to participate in developing some innovative good-intentioned technology to advance the greater good? Or embrace that lab coat my friends arbitrarily assigned me to 9.5 years ago and do some research to solve our problems? Perhaps. But what I resent as much as my complicity, is the myth of technological salvation that formed the foundations of my education, I resent that it stifles challenging introspection of the darkness within humanity from which oppression emerges. We are trained to assume that our environmental, economic, social, psychological issues can be reframed as technical problems to solve; therefore technology is the solution to everything. While technology can be part of the solution, the “salvation” rhetoric people use around it side-steps the real problem that is one of the human spirit rather than technical. Reframing problems stemming from the human spirit as mere “technical problems” to solved be technology doesn’t address the core issue of our fallen relationships the earth, each other, the Creator. Even worse, it dissolves these relationships: the land and people become resources to exploit and variables to optimize as sacrifices to our technological god in hopes that appeasing it will bring about our salvation (meanwhile giving us license to be complacent whilst we await the coming of our technological Messiah). If decolonizing is about healing relationships, technological mindsets are expressions of neocolonism, perpetuations of colonialism.

III. Work

There is so much work to be done to heal the pathological perversions that affirm death over life (necrophilia over biophilia) in our social and natural environments. In this regard, food is an obvious entry point for healing work. There is so much work to be done to disentangle myself from the ill effects of a globalized food system, yet we are all complicit in it just by surviving. Everyone physically, socially and culturally engages with food, yet food must come from the land. Food is truly at the intersection of people and earth.

Out of this struggle, regenerative agriculture materialized as an opportunity for praxis. Regenerative agriculture is a philosophy of land management and food production that reverses the damage we have done to land by drawing on inspiration from natural ecosystems. In many ways, regenerative agriculture echoes the sentiments of decolonization, by collaborating with nature rather than dominating, exploiting, or owning (colonizing) it. From my two pronged exploration of decolonization and regenerative agriculture this season, I now see that social justice and reviving land as two dimensions of one process that is restoring right relationship.

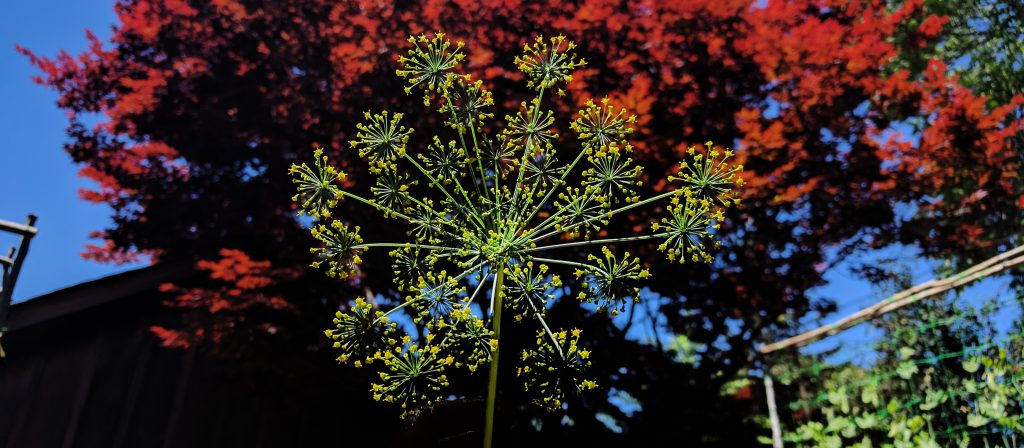

Which leads me to the vegetable growing part. This season, I joined a vegetable gardening company that envisions a full utilization of public and private spaces in the city towards the generation of nutritionally dense local food. I believe their aspirations not only to divest our consumption from unsustainable systems, but to advocate for food security, transform scarcity mindsets to abundance mindsets, and cultivate respectful relationships between city-dwellers, pollinators, and the land. Like food, gardening is at the intersection of so many things that matter to people. Gardening is wellness (health, nutrition, physical activity, opportunities for intergenerational connection). Gardening is activism (an act of resistance, empowerment, environmental stewardship). Gardening is art; self-expression in collaboration with nature over 4-dimensions of space and time. In contrast to our own pursuits of permanence through conquest, accumulation, and legacy, a garden shows nature’s embrace of impermanence.

While the aforementioned lofty convictions of ~relational healing~ are guiding principles for finding work, to make a direct link the contents of the daily grind to that vision is almost laughable. (Consider that moving soil around, defending ground cherries from squirrels, mixing worm-poop with chicken-poop, reseeding carrots for the nth time.) But I believe the mundane and the monotonous are sacred. Its in the mundane and monotonous where the preciousness of a relationship is forged. The work of tending a garden has brought me closer to the Spirit than any church service, revival conference, alter call, missions trip, ever has [1].

A friend and I recently agreed on how academics can articulate the problem so well, yet at the end of the day, their ideas for “praxis” sound so trite, so unscalable, and are so full of holes. I must admit that I feel the same way about my attempts at turning theory to practice [2]. But aren’t desires for “logical consistency”, “practicality”, “efficiency” and “scalability”, the very values from the dominant power structures and systems that I seek to resist? Isn’t it funny how I keep discrediting the technological mindset, but continue to viscerally crave for universal technological solutions to problems of the human spirit? The values of this sickly dominant culture has such a strong grip on me, it’s hard to imagine alternatives even as I try.

Ultimately, praxis is not about universal solutions but continual “action and reflection on that action” (Evangelical Postcolonial Conversations, 194). The process of reevalulating new information and experience, discerning their implications, and acting on the resulting convictions means that I am living on shifting ground. I am even less sure of my future than I was in those last high school days. I persist in faith that the Creator Who will animate and bring to life new ways of being that I would not be able to anticipate.

I am convinced that where I was this season was where I needed to be and I am thankful for the ecosystem of interactions between the divine, the earth, and fellow earthlings that have made it possible.

[1] While those may be authentic expressions of faith for many people, I hope that we also have the capacity to imagine our work being an authentic expression of faith.

[2] Actually, I have learned in the past few months that regenerative agriculture and gardening are worlds apart. Moving forward, I aspiring “regenerative” gardeners (aka myself) need to bridge this gap by advocating for closed-loop nutrient cycles and building soil health; but that elicits a whole other blog post.

These days, I feel more than ever work as an expression of faith, living as an expression of hope, and sorrow as an expression of love.

Resources

Some mentors that are keeping my sane during my ~2 hour commutes to work this season:

- Sacred Earth, Sacred Community: Jubilee, Ecology, Aboriginal Peoples [Text]

- Evangelical Postcolonial Conversations [Text]

- Abraham Joshua Heschel: The Prophets [Text]

- Hosea [Text]

- Charles Eisenstein: Living the Change [Interview]

- Thomas Ponniah: The Global Break Books Project [Lecture]

- Philosophize This!: Michel Foucault [Podcast]

- Curtis Stone: What Permaculture Got Wrong [Video]

- Richard Perkins: In Response to What Permaculture Got Wrong [Video]

- Thomas King: Green Grass Running Water [Text]

- Wisecrack: Why Thanos Changed [Video]

- Bill Mason: Waterwalker [Film]