Book Report: The Art of Loving

There is a core idea I try to live by that I couldn’t quite put into words… until this one summer afternoon some two years ago when I discovered Erich Fromm at a second-hand bookstore in Canmore. It so happens that Erich Fromm had already put into words my impressions and intuitions in his succinct little book, the Art of Loving … before even my mother was conceived.

An organized mind is a way to my heart. In this respect, The Art of Loving had me at “Table of Contents”. Fromm’s train of thought progresses quite logically, and this post will roughly track his trajectory:

- I. Is Love an Art?

- II. The Theory of Love

- 1. Love, the answer to the Problem of Human Existence

- 2. Love between Parents and Child

- 3. The Objects of Love

- III. Love and its Disintegration in Contemporary Western Society

- IV. The Practice of Love

Yep, I just quoted the table of contents; this book needs to issue a restraining order on me, lest I quote the entire thing.

Symbiotic Union (Section II.1)

Self-awareness is a property of humanity that is both empowering and isolating. Self-awareness enables us to understand ourselves as the “human”, the individual, separate from the rest of humanity. However, by virtue of understanding ourselves as separate from all others, we must accept the corollary that we are fundamentally alone. The helplessness that arises from existential dread of separation creates a demand for its nullification, and “the basis for our need to love lies in the … need to overcome the anxiety of separateness by the experience of union” (53).

This need is satisfied in various socially and psychiatrically unhealthy ways that Fromm calls symbiotic union. Symbiotic union is the phenomenon that arises from multiple human beings addressing their own respective states of separation by “identify[ing] themselves with each other”, essentially “solv[ing] the problem of separateness by enlarging the single individual into two” (46). Symbiotic union is essentially glorified codependence. A mutually beneficial relationship where individual use one another to their own benefit, without concern for the integrity or the individuality of the other (17). Fromm claims what most people—particularly Westerners—would consider “love”, is actually “symbiotic union”. Yet, to claim that something so selfish as symbiotic union as love is not only unhealthy, but altogether toxic:

“Selfishness is born out of neurotic ‘unselfishness’ … [unselfishness] is often the one redeeming character trait on which such people pride themselves. The ‘unselfish’ person … ‘lives only for others’, is proud that he does not consider himself important… he is pervaded by hostility towards life and that behind the façade of unselfishness a subtle by not less intense self- centeredness is hidden … [for example] the ‘unselfish’ mother … is worse [than the selfish one], because the mother’s unselfishness prevents the children from criticizing her … [the children] are taught, under the mask of virtue, dislike for life.” (52)

To claim that a symbiotic union with someone as “love” is not only a misconception, but a bastardization of what love ought to be.

Love as it ought to be (Section II.3)

By approaching this lofty topic from the psychoanalysis perspective of his training, Fromm is able to ground the radical implications of his thesis:

“If a person loves only one other person and is indifferent to the rest of his fellow men, his love is not love but a symbiotic attachment… If I truly love one person I love all persons, I love the world, I love life. If I can say to somebody else ‘I love you.’ I must be able to say, I love in you everybody, I love the world, I love life. I love through you the world, I love in you also myself.” (39)

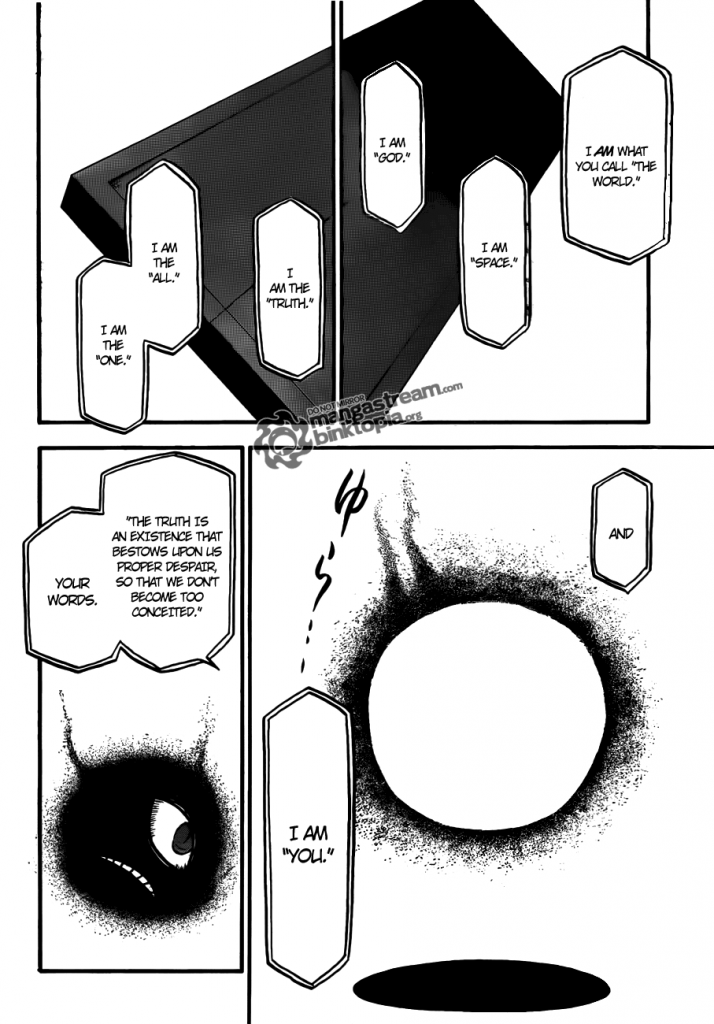

Aside: does this not sound like … Full Metal Alchemist???

That is to say, love that excludes any other human is not only not idea, but downright pathological. To love your children, your spouse, your family, your friends exclusively is pathological. This is deeply disturbing seeing how, these days, we see exclusive love is as a good thing; in fact, “most people believe … that it is a proof of the intensity of their love when they do not love anybody except the ‘loved’ person” (39). Thus, exclusive love—the love of your family, your children, your spouse, your friends at the expense of others—has not only been normalized and socialized, but even glorified.

Mature love, or in more medical terms, “unpathological” or “normal” love, is then, what Fromm considers what love ought to be (the “Platonic Form” of love, if you will). The mature lover loves life itself, it loves “the all” (humanity) that “the separated” (a human being) refers to. This challenging view of what “normal” ought to be is so central to Fromm as a person and as a psychoanalyst that he appends a collection of critical essays with this epilogue:

“The fundamental problem, I believe, is the opposition between the love of life (biophilia) and the love of death (necrophilia); not as two parallel biological tendencies, but alternatives: biophilia as the biologically normal love of love, and necrophilia as its pathological perversion, the love of an affinity to death. Biophilia and necrophilia often are found together in the same person … to see this struggle, and to will the victory of one’s own love of life against its enemy.” (The Crisis of Psychoanalysis, 192)

Love that is not biologically normal love is actually necrophilia. Intense.

Objects of love (Section II.3.a-e)

In Chapter II.3, Fromm elaborates what this pathologically healthy or normal love ought to look like for each distinct relationship pairing, or “objects”: Brotherly, Motherly, Erotic, Self, and God. Immediately, fellow C.S. Lewis fan-children will recognize that Lewis’ The Four Loves follows a nearly identical organizational structure, invoking Storge, Philia, Eros and Agape.

Both Fromm and Lewis a similar argument structure: for each type of relationship, they begin by addressing the unique nature of that type of relationship, then lead the reader to realize the universal potential of that relationship if the love stems from a “Love of Life”, for Fromm, or “Divine Love”, for Lewis.

| Relationship | Love of Life (Fromm) | Divine Love (Lewis) |

| Brotherly Love

(love between equals) Philia |

“Brotherly love is love for all human beings; it is characterized by its very lack of exclusiveness. If I have the capacity for love, then I can not help loving my brothers. In brotherly love there is the experience of union with all men, of all human solidarity, of human at-onemoment. Brotherly love is based on the experience that we are one.” (39) | “We think we have chosen our peers. In reality … Friendship is not a reward for our discrimination and good taste in finding one another … It is the instrument by which God reveals to each the beauty of all the others. … by Friendship God opens our eyes to them.” (The Four Loves, 126) |

| Motherly Love

(love for the helpless) Storge |

“A woman can truly be a loving mother only if she can love; if she is able to love… other children, … all human beings.” (44) | |

| Erotic Love

Eros |

“Erotic love is exclusive, but it loves in the other all of mankind, all that is alive… I love from the essence of my being–and experience the other person in the essence of his or her being. In essence, all human beings are identical. We are all part of One; we are One.” (46) | “[Eros] has over-leaped the massive wall of our selfhood; … planted the interests of another in the center of our being. Spontaneously and without effort we have fulfilled the law ([albeit] towards one person) by loving our neighbor as ourselves. It is an image, a foretaste of what we must become to all if Love Himself rules in us without a rival.” (The Four Loves, 158) |

| Self-Love | it is a “logical fallacy… that love for others and love for oneself are mutually exclusive … If it is a virtue to love my neighbour as a human being, it must be a virtue–and not a vice–to love myself, since I am a human being too. There is no concept of man in which I myself am not included.” (49) | |

| Love of God

Agape |

“God becomes … the nameless One. … the unity underlying the phenomenal universe….; God becomes truth, love, justice. God is I, inasmuch as I am human” (59)

“The love of God is … the act of experiencing oneness with God” (65) |

“Only by being a manifestation of His beauty, lovingkindness, wisdom or goodness, has any earthly Beloved excited our love … All that was true love … on earth was far more His than ours, and ours only because His. … By loving Him more we shall love [any earthly Beloved] more than we now do.” (The Four Loves, 191) |

Why read anything when Full Metal Alchemist explains everything …

Despite the similar flavour of their conclusions, it’s interesting and important to note that whereas Fromm claims the “Love of Life” is biologically normal and only perverted by society, etc. (The Crisis of Psychoanalysis, 192), Lewis thinks that instinctual love is naturally fallen/perverted and only redeemable by divine intervention (The Four Loves, 26).

Love and Society (Section III)

Fromm is particularly critical of the Western Society he was part of. It’s easy to understand how his theory of “separation anxiety” facilitates the adherence to the uniformity that is dictated from above (as in collectivist societies). However, the West should not be too smug. Despite having the “freedom” to exercise individuality, innate separation anxiety forges nearly identical results voluntarily. Here,

“Man becomes a ‘nine to fiver,’ he is part of the labour force… has little initiative, his tasks are prescribed by the organization of the work … they all perform tasks prescribed by the whole structure of the organization, at a prescribed speed, and in a prescribed manner. Even the feelings are prescribed: cheerfulness, tolerance, reliability, ambition, the ability to het along with everybody with friction. Fun is routinized in similar …. From birth to death, Monday to Monday, from morning to evening—all activities are … prefabricated. How should a man caught in this net of routine not forget that he is a man, a unique individual … with the longing for love and the dread of separateness?” (16)

Touché.

For Fromm, falling short of the standard of mature love is in part due to our normalized but pathological states of being. For Lewis, this pathological state, the disease is sin, “Being a Fallen Man” (The Four Loves, 80). Both point to the futility of striving for the best of human potential in the context of our social systems and the fallen world, respectively:

| “Is the alienated person with little love and little sense of identity not better adapted to the technological society of today than a sensitive, deeply feeling person? When speaking of health in a sick society, one uses the concept of health in a second, sociological meaning, as denoting adaptation to society. The real problem here is precise that of the conflict between “health” in human terms and “health” in social terms; a person may function well in a sick society precisely because he is sick in human terms…. Was not a sadist quite effective in the Nazi system, and a loving person quite unadapted?” (The Crisis of Psychoanalysis, 36) | “Medicine labours to restore ‘natural’ structure or ‘normal’ function. … who, in Heaven’s name, would describe as natural or normal the man from whom [greed, egotism, self-deception, and self pity] were wholly absent? … We have seen only one such Man [Jesus Christ]. And He was not at all like the psychologist’s picture of the integrated balanced, adjusted, happily married, employed popular citizen. You can’t really be very well ‘adjusted’ to your world if it … ends up nailing you up naked to a stake of wood.” (The Four Loves, 81) |

Ultimately Fromm concludes that “the principle underlying capitalistic society and the principle of love are incompatible” (110), that “to analyze the nature of love is to discover its general absence today and to criticize the social conditions which are responsible for this absence” (112).

Given Fromm’s pessimistic view of society, I find it surprising that he could have enough faith in humanity to urge

“those who are seriously concerned with love as the only rational answer to the problem of human existence must, then, arrive at the conclusion that important and radical changes in our social structure are necessary, if love is to become a social and not a highly individualistic, marginal phenomenon. … to have faith in the possibility of love as a social and not only exceptional-individual phenomenon, is a rational faith based on the insight into the very nature of man” (112).

As it is, I’m not as optimistic as Fromm is about the enlightened subset of humanity imbued with “serious concern with love as the only rational answer” (112)… or any another other manifestation of humanity at its best.

What I find more disturbing, still, is Jacques Ellul’s idea that sin is emergent from the society, that “the city” can take on a selfish character of its own and perpetuate herself without the awareness of its members:

“Here we have a sign of a social sin … the social group which the city represents is so strong that it draws men into a sin which is hardly personal to them, but from which they cannot dissociate themselves even if they so desire. Individual virtues are engulfed by the sin of the city. … No one, really, has individually violated, by his own decision, God’s law… They have not each committed their own particular sin, but they have participated in the sin of their society. … No one commits the sin, but it is still committed. No one does evil, everyone wishes for the best … Yet, look at the results: even more slavery… Slavery tolerated. Human relations destroyed in the anonymity of the great city… evil is still committed.” (The Meaning of the City, 61-67)

Yet, this is closer to my experience. Somehow the emergent sin from All is seems greater than the sum of the individual sins of each.

The Practice of Love (Section IV)

I believe the logical fallacy that causes us to resist such a universal understanding of love is our assumption that love is a finite resource. After all, if we think of love as “action”, and action as something that involves energy. Since energy follows the law of Conservation of Energy (which states that all the energy in an isolate system remains constant, that energy cannot be created or destroyed but only transformed from one form to another), it practically follows that there is such a “Law of Conservation of Love”. If this law existed, it would state: “within my limited capacity to love, I can only transform my love for one things to another.” Therefore, by loving something less, I have a greater capacity to love someone else more. Love is completely reduced to a summation of actions at best, and transactions at worst.

However, if love is an orientation, a state of being, an art … then love can not only be created, but creative:

“He gives of himself …; he gives him of his joy, of his interest, of his understanding, of his knowledge, of his humour, of his sadness—of all expressions and manifestations of that which is alive in him… [in doing so] he enriches the other person, he enhances the others’ sense of aliveness by enhancing his own sense of aliveness … he cannot help bringing something to life in the other person … he cannot help receiving that which is given back to him. Giving implies making the other person a giver also and they both share in the joy of what they have brought to life … love is a power that which produces love.” (21)

Fromm himself would not understand it as such, but I suppose he would allow me to understand that “God becomes truth, love, justice. God is I, inasmuch as I am human” (59), as a reference to Jesus Christ. God Himself became the only “normal”/non-psychopathic Human in existence, gave “all expressions and manifestations of that which is alive in Him” (21) which culminated in the ultimate expression of His (re)creative love. This is the potential of human love fully one with the divine.

From it I know that I and the humanity I am part of are loved beyond my capacity to love back.

From it I know that I and the humanity I am part of are capable of greater capacity to love.

It inspires me and the humanity I am part of “to long for the attainment of the full capacity of love” (60).

I guess you could say that I am pleasantly Surprised by Hope …a most pleasant reminder for Easter 🙂