Gjøvik’s Baobab Catastrophe

In Norway (at least the part we were in), if you are registered as a farm, you are audited from time to time for compliance to their rules (which mainly have conventional monoculture farms in mind) otherwise you lose your “farm” status and its associated privileges. One of the requirements is to keep a mowed field of a certain size. Besides, it’ll make future earthwork projects much easier to follow through with.

In theory, goats are great at eating these small fast-growing trees on fields. However, there are prerequisites to goats. This includes (a) fencing the field and (b) cleaning/making room in the barn for the goats (which, if you remember how much garbage was in the shed, is not a simple feat).

In the meantime, WWOOFers make ideal surrogate goats [1]. That is, we needed to (c) manually keep the trees from growing too big while we are waiting on (a) and (b) to happen. Spoiler Alert: We never made it to (a), maybe a day an a half was dedicated to (b), but the majority of our labour was spent on (c). In fact, this entire post is about (c).

[1] I mean, technically, if any human were to do it, Tim and I would have an advantage, being born in the Zodiac year of the goat and all … but that would just make us humans in sheep’s clothing 😉

The thing is, when you try to keep a field a field, Nature tries to reclaim it as a forest. Trees will start growing on the field if you don’t maintain it. , once these tree roots get established, they become inaccessible–even to goats–and a living nightmare to get rid of. (Though, looking at these pictures, it’s hard to imagine, any tree standing a chance against goats…)

Our plight was like holding onto the front of a losing battle. There was no way we could get ahead of the trees: no way we could do block them from getting their resources, no way we could preemptively damage their weapons refinery or whatever.

We were ill-equipped for this war. In our arsenal of weapons, we had: an axe, a shovel, a farmspear, and our (gloved) bare hands. Since we only had one or two of each weapon to share between the four of us WWOOFers, we each ended up specializing in different tools.

The American WWOOFer’s weapon of choice was the axe. Soooo cool <3.

The French WWOOFer used her bare hands. She actually preferred it. Craaaaazy.

As, indicated in the feature image, I loved the farm spear.

Tim was probably the most versatile because he always let the rest of us choose what to use. He often used a big shovel to get started, and then used gloved hands to dig out the roots.

All this is to say, our methods were primitive and barbaric and brute force. Definitely the underdogs. (Though, seeing as we, WWOOFers, were dropped in from North America and France, less-biased news coverage could make the case that we are the invasive species, not the trees!)

The trees, on the other hand, have millennia of adaptive experience and sophisticated technology of their own: roots. Interconnected roots, deep roots, roots wrapped around rocks….

And if you failed to pull out the whole root, the tree will undoubtedly spring up again … and worse yet, with roots that are even harder to pull out. One would think that leaving the roots in the ground would be okay since there are no leaves to photosynthesize, right? Think again. Trees communicate with each other, and indeed, pass nutrients to each other through their roots.

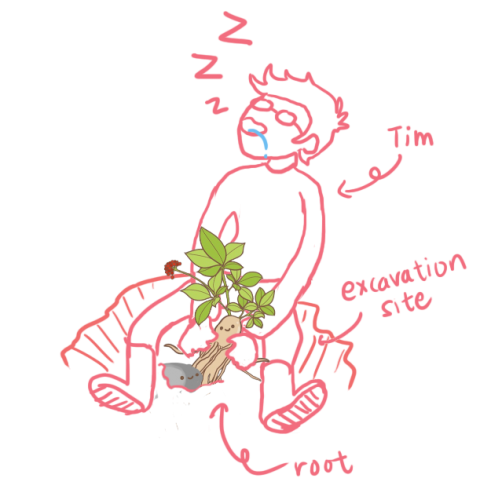

There was this one ridiculously hot afternoon when we went back out on the fields after lunch. 45 minutes into it, another WWOOFer and I were too exhausted to continue. We reconvened and decided to head back to the house and try again another day. Knowing that Tim (undoubtedly the hardest working of all of us) would probably want to continue working, we went over to let him know that we were giving up… only to see this:

The poor man fell asleep halfway through excavating a root.

We all helped him finish off that tough cookie of a root and went back to our WWOOFer quarters.

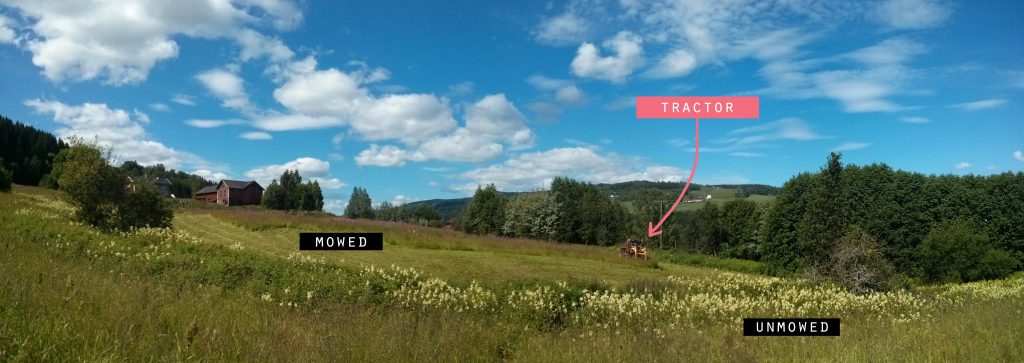

While there was no way we could get ahead of the trees, we did have one secret weapon on our side that helped us keep up with them–the tractor!

In organic/permaculture farming, tractors are used as little as possible as the soil can get compacted under their weight. But with large fields like this, it’s beneficial to get a tractor to mow the field once or twice a year so that the cut grass can add biomass and nutrients back into the soil. This dilemma, too, shall pass when they goats come–they will be more than capable of keeping a field mowed without a tractor!

Wheelbarrowing through tall grass.

For us surrogate goats, the mowed lawn benefits us greatly. While the tractor by no means pulls out tree roots for us, it addressed many other problems that stunted our progress prior. Before mowing the field, it was difficult to identify trees in the midst of so much tall grass. If a root was left in the ground and we left for two seconds to find a tool to dig it out, we wouldn’t be able to find the stump after! Furthermore, when you needed to excavate the region around the root, you’d have to dig up a bunch of tall grass and weeds as a prerequisite. Not to mention, tall grass was a nightmare to push wheelbarrows full of tree corpses through.

However, the day our hosts mowed their “lawn”, it was apparent to us just how much more work there was to do. The tractor conveniently mows the grasses and weeds and leaves the tree behind sticking out. Now there was a visible indicator of how much we had left to do…. and there were a lot.

… You can only reaction my reaction when our host told us there they had a second field across the street that needed the same treatment.

Royally pooped.

If any task could have broken our morale, it would have been this one. There was a deep sense of futility associated with this job. We knew if our hosts didn’t get the goats soon, the trees will inevitably win the war. The group of WWOOFers before us–“Spanish Boys” as our host affectionately called them–had already laboured on this task before we arrived…. and I wonder how many more will have to endure this plight before the fields get fenced and goats are brought in!

I recently watched The Little Prince (2015) (based on the book of the same name) again, and it gave me fond memories and a little more insight to our tree-pulling plight. Remember how the Little Prince wanted the Pilot to draw a sheep to deal with the baobabs growing on his planet:

“Indeed, as I learned, there were on the planet where the little prince lived– as on all planets– good plants and bad plants. In consequence, there were good seeds from good plants, and bad seeds from bad plants. But seeds are invisible. They sleep deep in the heart of the earth’s darkness, until some one among them is seized with the desire to awaken. Then this little seed will stretch itself and begin– timidly at first– to push a charming little sprig inoffensively upward toward the sun. If it is only a sprout of radish or the sprig of a rose-bush, one would let it grow wherever it might wish. But when it is a bad plant, one must destroy it as soon as possible, the very first instant that one recognizes it.” (The Little Prince, 17)

Such is the reality of maintenance-based work. It’s not glamorous, it leaves no legacy, yet it’s necessary and vital to building a permaculture farm, one’s character, and indeed, entire planets.

“Now there were some terrible seeds on the planet that was the home of the little prince; and these were the seeds of the baobab. The soil of that planet was infested with them. A baobab is something you will never, never be able to get rid of if you attend to it too late. It spreads over the entire planet. It bores clear through it with its roots. And if the planet is too small, and the baobabs are too many, they split it in pieces… You must see to it that you pull up regularly all the baobabs, at the very first moment when they can be distinguished from the rosebushes. It is very tedious work. … Sometimes there is no harm in putting off a piece of work until another day. But when it is a matter of baobabs, that always means a catastrophe.” (17)

Source: Lectures Bureau

“It is a question of discipline,” the little prince said to me later on. “When you’ve finished your own toilet in the morning, then it is time to attend to the toilet of your planet, just so, with the greatest care.” (18)

I look back at my time in the fields fondly because the capacity to care for the toilet of our world is such a great privilege.

“Children,” I say plainly, “watch out for the baobabs!” (19)